The Joy Menu #58: Shadow

Maybe it’s here that I attach mythology to his life as an artist — a counterpoint to this tension, to this heaviness, to the darkness which blows in unwelcome like a storm.

Dear Creators,

It’s harder to write about the difficulties. Easier to rest in reverie for the beauties of a man. Harder: the years he was unhappy. And the unhappiness that bled into us, his family, his kids.

Though bled is the wrong word. Bled implies a seeping, a slowness. Bled implies physical rupture.

It wasn’t that.

If anything, he was a lion and the unhappiness was brooding, and its rupture was explosive. A long, low growl — a warning — and then an eruption. A roar. A rage-filled release, and then… and then let him be and, cowering elsewhere, wait for the clouds to part.

We are in the small living room at the front of the house. Big window open to the other condos. Sun bright, as always; carpet brown, walls beige, furniture dented by hot wheels and dog teeth.

We’ve been fighting all morning, now there’s a moment of calm. My brother plays the Nintendo, which our grandparents gifted us at their 50th wedding anniversary and which my father hates.

Benny stands while he plays, and I sit backwards on the couch, which runs along the front window, one hand on the dog’s back, the other picking my nose. Sarah, the oldest, comes in. “Gross,” she says; “Shut up,” I say.

She slugs me; I lunge toward her, fall onto the coffee table, yell out in protest, and knock into Benny’s back — he bursts into tears. My father rushes in like a Titan riding a gust of hot wind, enraged, already yelling, a flat hand out reaching for an ass, a thigh, we run...

I know there is never enough money. I know he is asking, asking, for help — from parents, siblings, friends, the universe. I imagine the weight of three young children, a mortgage, a job that feels grueling, uncreative, strict, bosses that take what they can and leave him only the scraps.

His parents, brothers, cousins, thousands of miles (and thousands of dollars) away.

I know he comes home drained; I know he leaves early in the morning, before we can even kiss him.

I know we fight noisily and unendingly, three kids with big mouths and clashing personalities, living in 1,000 square feet, sleeping in bunk beds, elbowing each other for attention, definition, self-expression.

Maybe it’s here that I attach mythology to his life as an artist — a counterpoint to this tension, to this heaviness, to the darkness which blows in unwelcome like a storm.

On Saturdays, he takes us to the Fine Arts Center, next to the Castle Park, and we paint and draw, build clay sculptures which we cook in the kiln and bring home for display on the bookshelves which line the living room walls.

During summer: art camps, watercolors, sketching, then acting, then music. He’s happy to drive us, asks us what we’re making, smiles and encourages our creations.

When his mother sends us sketchbooks and colored pencils, my creations turn as abstract as the art (his art) which covers our condo walls: I cut a jagged line across a naked sketchbook page — a dagger cut in red.

“Here,” I show him. “I’m done.”

Love it, he says. Keep going.

I fill the book with lines, scratches, scribbles. It feels good to draw. To curl myself in the corner and cover page after page with whatever comes out when I stop thinking and just draw.

I wonder: Was this art for him, or for me? (Is there a difference?)

Is the artist a calmer, more balanced child? Does the artist see in another artist a calmer, more balanced father?

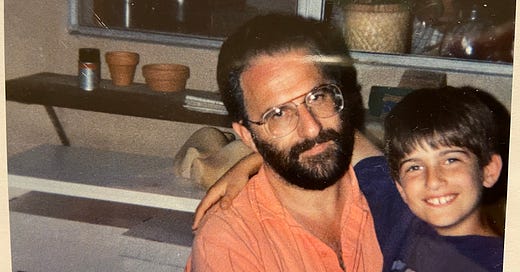

Do I, a child predisposed to dreaminess and creativity, see this other father as a version I’ve missed out on? A father not defined by fear and stress, anger and resentment, but a man living in his essence, free to spend his time shaping and forming, writing and reading, playing and sculpting.

A father who is free on weekends to sit with us and make things.

The day he takes us to the field next to the 5 freeway to play soccer. All three of us!

Straps on our cleats, pulls on the tight fitting shin guards and the thick knee-high socks. Runs us in circles on the sweet dew-wet grass, showing us better ways to dribble and block and pass.

All us kids, all his kids, at the park, playing soccer! The early morning wake-up, the undivided attention, the drowsy nap in the car on the drive home…

A single day, a lone memory. A scrap. Does its rarity speak to the absence of other such days?

And whose fault is that?

Where to lay the blame?

He, too, misses out on the play, the easy times, the resolutions, the giggles, kid-cuddles, wiped tears — everything else that colored those quick-passing days.

Where was he?

Tired from work?

Exhausted from carrying the anxiety he collected like a paycheck, in exchange for supporting us?

This is not the whole story. It is a shadow of the story.

A shadow cast by his bigness, his personality.

A shadow cast by his choices — what was drawn and what wasn’t. Each colored pencil stroke pulled across a blank, open page. A page which is now no longer blank.

Perhaps the dagger cut is a cut through the tension, or through to the other side of the tension. The shadow of the tension. Which is itself a darkness, a stain; cut in his shape, and in the shade of his trembling, unexpressed love.

A dagger cut — or a bending man.

A father kneeling toward his son holding the thorny stem of a creased and folded rose.

Onward toward creative joy,

Joey

"A single day, a lone memory. A scrap. Does its rarity speak to the absence of other such days?"

"A single day, a lone memory. A scrap. Does its rarity speak to the absence of other such days?"