The Joy Menu #43: Fertilizer (I)

"Half the week he was away, and busy: a thick-armed immigrant with a product to sell. The other half, he was home, and he was present."

Dear Creators,

For years, my father had a “normal” job, which (need I explain?) meant he was gone all day, out of view, away from us, tucked into a grey cubicle, or a brown one, or maybe beige — in nondescript office buildings, buried in corporate parks, doing various kinds of work, some of which he carried in long plastic tubes from the condo to the car and back into the house at night, and others of which we never saw, which disappeared as soon as he got in his red Chevy to commute home at the end of the day.

But around the time I started high school, he switched careers and began a new business, entrepreneurial by nature, more transparent, more concrete, and in our middle class suburban community nudged between beach towns, freeways, and shopping malls, unusual: selling micronutrient fertilizer to small and medium-sized farms across the West. I’d tell my friends, suggestively, that my father made a living driving from Mexico to Canada shilling white powder from the back of a truck. It was a joke — but only nominally.

First, Suburban’s aren’t trucks. And second, they don’t have ‘backs’: they have caverns. And his was full of heavy plastic boxes filled with fine powders, each labeled with the chemical symbol of the micronutrient packed inside: B (boron), Mn (manganese), Cu (copper). Our garage was also packed full of these containers, and talk over dinner switched from office politics to discussions of import taxes, shipping fees, crop yields, profit margins, fruit fly infestations, sample vials, pH levels, and more.

For the first time, I saw my father relaxed, engaged, full. And we saw him a lot.

In this new life, my father spent half the week on the road, and half the week at home.

Half the week, he slept in roadside motels in towns like Temecula and Bakersfield; spent his days chatting with growers, building connections in agricultural communities, kicking up dust along the dirt roads of the California Central Valley.

And then the other half of the week, he was tightening his sneakers at the door before heading out to walk the Loop, or calling out to whomever was around before he left to run errand after errand: “Going to the post office if anyone wants to come?” or “Anybody up for a movie?” or “Come, we can run by the auto shop and then we’ll grab a bite.”

Half the week, he convinced recalcitrant farmers to give him an acre or two, so he could show them what boron could do in the smallest trace quantities to reinvigorate their tired soil. Then he’d see blockbuster movies in sleepy backcountry cinemas, or catch live bluegrass at the local honky tonks (later, driving near home, a song would come on and he’d say: “I saw them perform at Buck Owens’ Crystal Palace…”).

And the other half, if you needed something, he was eager to get it: batteries, a graphing calculator, a prescription that needed picking up. “I got it,” was his refrain, as he offered to drop us at school, or to pick us up from a friend’s, or to bake mediocre chicken (bathed in a Pyrex full of supermarket salsa), or to shrink our new clothes in the dryer, or to set his wire-framed glasses down, lay his book to the side, and have an impromptu (and much needed) chat.

Half the week he was away, and busy: a thick-armed immigrant with a product to sell. The other half, he was home, and he was present.

In those years, my father kept a list of films he wanted to see in a reporter's notebook by the door — next to his keys, his pants (never worn in the house), and the pack of Regal movie tickets he bought in bulk.

In those years, we bought a house — a “real” one, detached, with a garage and a second story (just like our friends and neighbors).

We got a new car. And then another one (this one for my mom).

In those years, he amassed an epic CD collection (more Classical box sets than Tower Records had in stock).

We got a family computer (the first not purchased with an employee discount).

And we flew to Belgium to see our grandmother (his mother) and to our uncles (my father’s brothers).

In those years, my father took my sister back East to visit colleges, and I got a drum set, and my brother got a BMX bike (and we both got electric guitars).

In those years, things seemed possible which before had caused us pain. Everything seemed different, accessible, flowing. (Though what, besides money, was?)

I wonder: what happens to the urge to make art when there’s no art being made?

And what of the maker? He or she who holds that urge?

I wonder: does it ebb, like a tide, waiting to roar back and cover the abandoned shore? Or does it die down, like a fever — expressed, sent from the body like a cough, or expelled passively like a hundred beads of sweat?

Is it consumed like adipose — metabolized, applied to other, more pressing uses within the hungry body? Or does it calcify, like scar tissues, all numbness and stiffness as the dead cells regenerate inside their fibrous casings?

I wonder: Does it fade or does it fester? Does it travel? Does it fight?

More than anything, at that time, what had been buried in my father seemed to begin to find ways out.

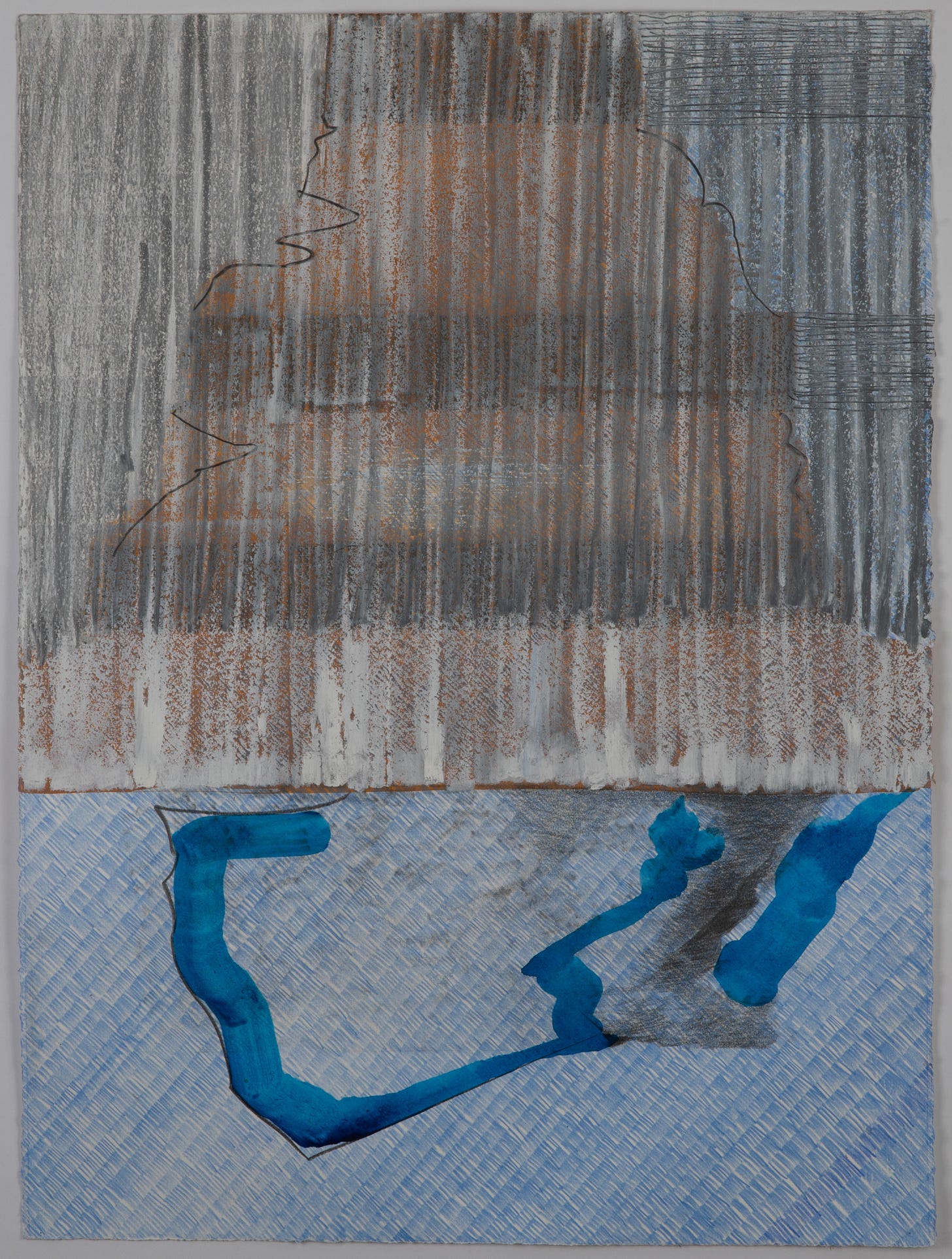

Urges fed in hibernation by the books, and films, and CDs; by the visits to museums, and concerts on tall stages; by the light whimsy of remembering great art seen and great performances witnessed; by the push for his kids to play the cello, the viola, and the violin, the drums, guitar, upright and electric bass; those urges which had perhaps always been seeds suddenly began to bloom in unexpected and arabesque ways: projects, none of which we expected, or could have planned for.

Projects born of those long subsumed urges.

Projects sprouting overnight, like mushrooms in a once-blank field.

More next week.

For now, onwards

toward creative joy,

Joey