The Joy Menu #17: Drawing

Your author remembers a visit home.

Dear Creators,

What does it mean to be an artist?

Was my father an artist?

Why was I always so fascinated with him having been an artist?

As a child, I carried that fact around like a secret in my pocket — abstract, unrelated to the images around me, separate, special, endowed with power — and it excited me.

“What’s your dad?”

“A city planner — but he was an artist.”

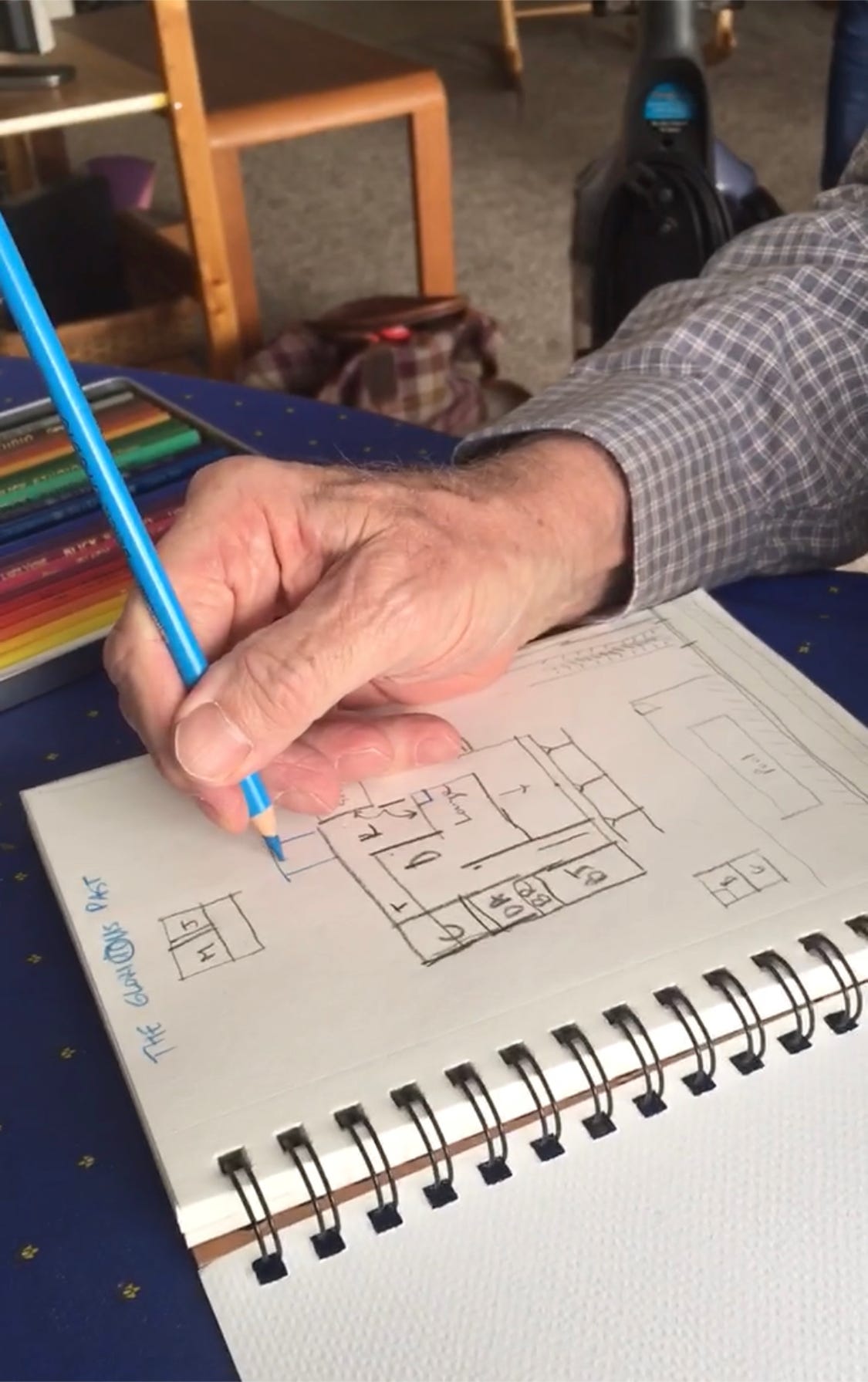

I watch him draw. He doesn’t draw often.

Outside, snow falls hard. The sliding glass doors to the balcony haven’t been opened since I arrived. Presumably they haven’t been opened in weeks. The balcony floor, through the misty glass, is a white sheet.

He refuses to go out. Refuses is a strong word; he’s a grown man, in the middle of winter and a long disease, his head shaved bald since the radiation eleven months previous. For some reason, he’s never owned a proper jacket. (In 30 years in California this was never an issue.) But this isn’t why. “You go,” he says to any suggestion of a walk, a drive, an errand.

But now he’s drawing: the strokes are strong, the lines confident.

Together, we spent thirty minutes on Google Maps, scanning the streets of his old neighborhood in Johannesburg on Street View, trying to find his childhood home. We’re having trouble. Everything is walled up, hidden from view. (“Was it like this back then?” “Yes, but the walls were shorter”). Still, something should be recognizable, we think.

He’s drawing a floor plan, an aid to help us find the house from above, from the perspective of the satellite photographs.

“The garage was here,” he explains. I watch the pencil swing back and forth, bold strokes, each line not exact, but cumulatively, together, creating a clear shape, a living picture. “Six or seven feet around from the fence, here.”

I could watch him draw for hours. I take out my phone, sheepish, to film.

I think: this drawing is not just this drawing, but the product of a hundred thousand drawings, though fewer than a half-dozen done in my line of sight, fewer than two dozen done during the expanse of my entire childhood.

“Ask your father; he’s the artist,” my mother would say when we came to her for help with a school project related to that creative act, or any like it: sketching, rendering, visualizing, designing.

Once, he helped me design and build my dream house (how I loved that foam board model; the house — not a winter-dweller’s home — was meant to be entirely walled in glass). Another time, we drew still lifes in the yard. But mostly, it was silent demurral, not even a “no.” “Dad? Will you help?” Something for her, not for him; something from another time.

You had to catch him — a quick cartoon on the telephone notepad; or even his signature on a credit card receipt: as explosive in form and power as a college sprinter leaping for a shopping cart before it rolls into the road. A rare thrill, an honor, to see such skill almost never used on sudden and surprising display.

Today, the floorplan; it’s not just a floorplan.

“There were steps down here; that’s where I fell and cut my hand on the coke bottle. And the workers’ house was back here; Jane on this side and Moffat on the other. And the pool — this is where we swam. We’d pull the car along the side here to park, and then we’d jump out and head right into the yard.”

This is our trip together, I realize. Our father-son trip to his childhood home. This is all we’ll get.

Pay attention. Watch him draw.

My patrimony of artistic appreciation: the museums we drove to in LA, the concert tickets (so many concerts!) purchased so we could attend. The classes, even as young as five: sculpture, a favorite (I remember the columns climbing upward, abstract in form, overlapping, while the other kids tried for horses, houses, familiar shapes), acting, music, dance.

It was the stuff of life, this engagement. Not meant to be an imposition or a direction, just a way of living fully; like eating well, sleeping in a comfortable home, spending Sundays out with our grandparents.

It was pure gift. Yet I struggled with romanticism: the draw of “being an artist.” Did I invent this path for myself? Did I pick it up from unspoken hints? Was it implied in the gloss of a wet-eyed stare?

We all want to be the object of parental love; was I seeking in the way I formed my identity to stand in this mold — The Artist — to grow like a bent tree toward this idealized objective? (Never requested, never explicit, never pushed; always understood, always aspired to.)

During my years of self-chastisement, of frustration, of self-perceived failure (not writing enough, not publishing, not “fulfilling my creative potential” — the quote my own), he would always say: “It’ll work out.” (Never judgemental, never cruel, never worried, never disappointed.)

That phrase, now, I see, did not mean art will work out. It meant life works itself out.

I generated my own black and white judgements. The phrase a Rorschach: you see in it what you need to see, house or horse or hearse or hell.

Looking forward: the artist I want to be I will be. Looking back: the man I am is the man I needed to become.

You had no designs; you did not draw me. I drew myself based on my own assumptions. Art not exempt from the bullshit of being human; no life outside the walls of living: driveway and pool, living room, trash cans, bedrooms, roof.

You provided the gift: access not to a heightened way of feeling, but to the tools to try and understand, and then to capture that understanding somehow.

To write about it. Or draw it.

It may not be a living, but it is a way to live.

Was my father not an artist?

We found his home eventually. (“There it is. That’s got to be it!”) We stared at it in the satellite image, and then switched to Street View. We looked at what we could see beyond the wall.

Was he misty-eyed? Was he sad? To stare across 10,000 miles and fifty-two years, from a snow-covered Ohio apartment building to a frozen image of a Johannesburg no longer his?

I stopped the video. I took the drawing. I still have it; dated and signed.

Happy Sunday, friends.

Onward to creative joy,

Joey